Samurai, British Museum

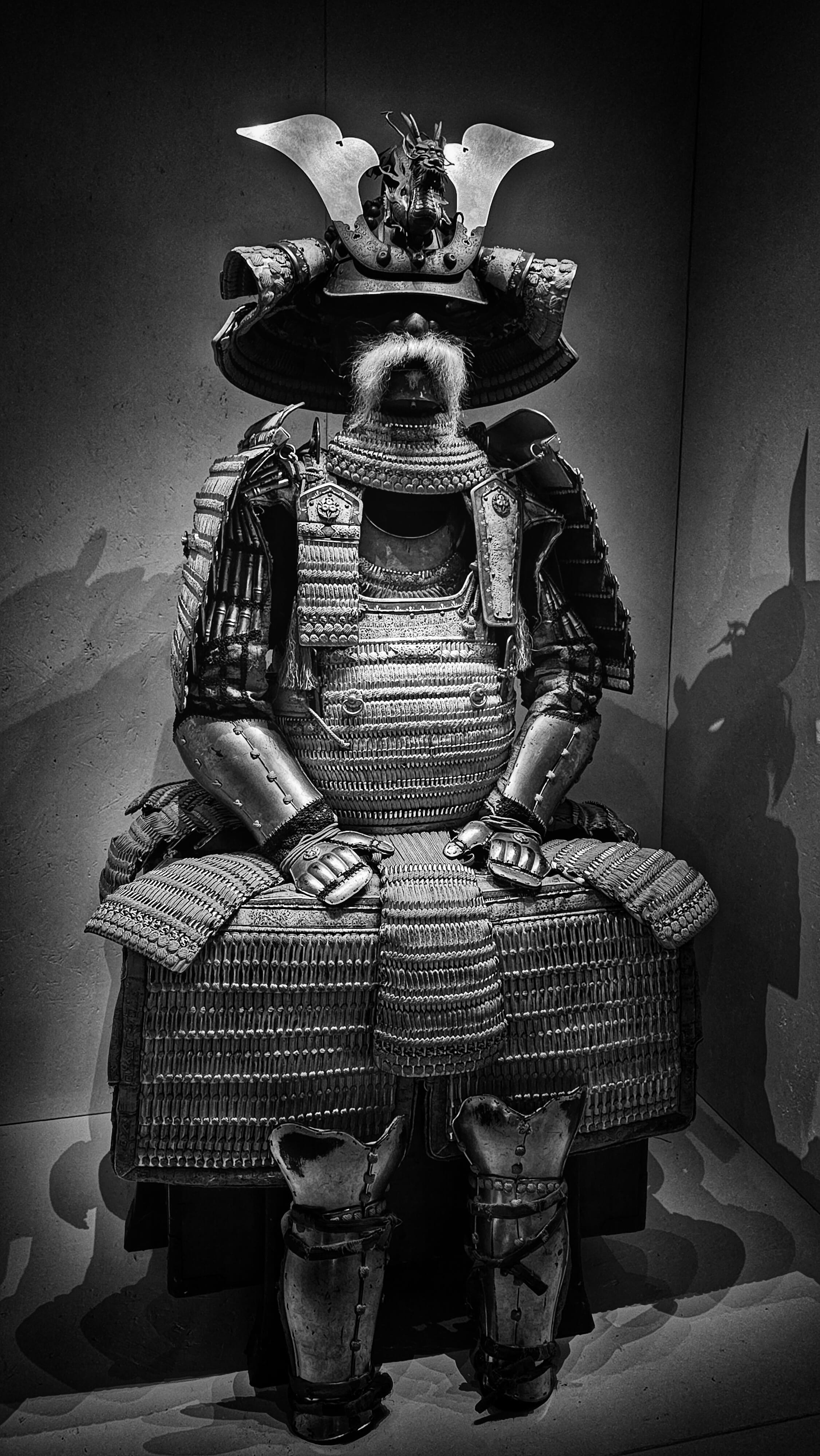

The British Museum’s exhibition Samurai presents a broad and visually compelling survey of Japanese arms and armour, situating the warrior class within both its historical and cultural contexts. Rather than focusing exclusively on battlefield function, the exhibition explores the evolution of armour as an expression of status, identity, and symbolism, particularly from the late Momoyama period through the Edo period.

The exhibition design is deliberately restrained and atmospheric. Low light levels and carefully controlled illumination draw attention to form, silhouette, and surface, allowing the sculptural qualities of the armour to take precedence. While this approach poses challenges for photography, it successfully reinforces the presence and physicality of the objects themselves. The decision to permit photography is particularly welcome, encouraging close engagement and extended study.

My own primary area of interest was, unsurprisingly, Japanese armour. While the exhibition includes a wide range of related arts, from woodblock prints to lacquerware and other associated material, this review inevitably places armour at the centre of attention. In this respect, the exhibition was particularly rewarding. I was pleasantly surprised by the quantity and quality of armour on display, especially given that outside of dedicated exhibitions the British Museum typically presents only a single suit or a very limited selection. For a self confessed armour specialist, the opportunity to study multiple examples within a single, carefully curated space was both engaging and satisfying.

The majority of the armours on display date from the Edo period, reflecting a time when armour increasingly balanced martial function with ceremonial and representational roles. This emphasis is well judged, as it allows visitors to appreciate the extraordinary craftsmanship achieved by Japanese armourers once the immediate pressures of large scale warfare had receded. Lacquer work, lacing schemes, helmet forms, and decorative fittings are presented not as embellishments, but as integral components of martial identity.

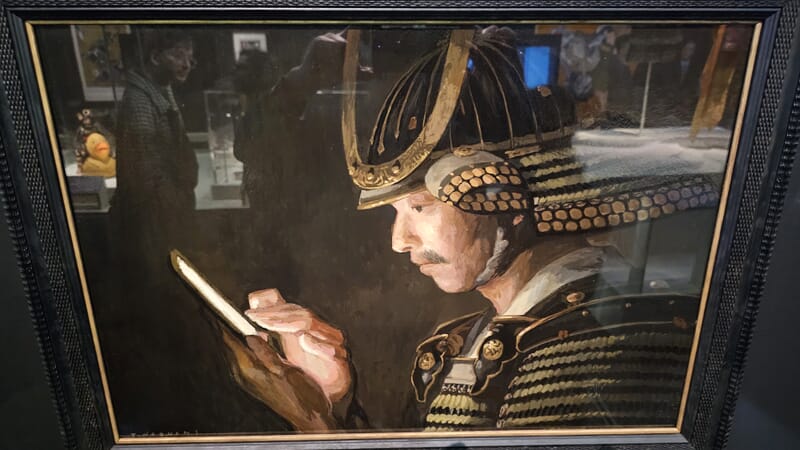

Alongside historical material, the exhibition incorporates a limited number of contemporary works and modern references, creating a dialogue between past and present. These inclusions are handled with restraint and serve to underline the continued influence of samurai aesthetics on modern visual culture, rather than distracting from the historical narrative.

Overall, Samurai succeeds in presenting Japanese arms and armour as complex cultural artefacts rather than static military relics. For both specialists and general audiences, the exhibition offers a thoughtful and visually arresting encounter with one of Japan’s most enduring historical traditions.

Selected Highlights

The works selected here are presented for their artistic value and the sophistication of their craftsmanship, rather than their practical function. Where exhibition catalogue entries are necessarily brief, I am often able to offer more detailed descriptive context. This is samurai art in its native form.

Kaga Armour

The museum catalogue describes this armour as a bulletproof cuirass embossed with a crest, dated broadly to 1600 to 1700. The first and most immediate impression, however, is that this is definitively a work of the Kaga province, which would place it more convincingly in the mid to late Edo period.

Armours of this type were often intentionally flamboyant. This raises the possibility that the cuirass a go-mai-dō 五枚胴 itself may be somewhat earlier and later adapted for more modern use, namely ceremonial wear. The dō is not technically embossed using uchi-dashi 打出 techniques, for which there is no clear evidence. Instead, the surface appears to have been built up through the application of additional plates, creating relief rather than true repoussé work.

The catalogue notes the use of leather, which may simply refer to the kusazuri 草摺, where this would be entirely typical. However, given the claim of ballistic resistance, it is also plausible that an internal layer of rawhide was lacquered onto the iron, adding further protection. Without physical inspection this remains an informed assessment based on period technologies.

The armour is very clearly Kaga 加賀国 made. Kaga became a refuge for armourers as demand declined during the long peace of the Edo period, with craftsmen relocating under the patronage of the Maeda clan. The resulting armours are characteristically bold and decorative. Key indicators here include the use of sawari alloy 佐波理 on the mae-dō, ivory kohaze in the mokkō form, yamamichi rolling mountain 山道頭 on the kusazuri , and the distinctive centralised Kaga maedate positioned above the kuwagata-dai.

Further decorative elements include ornamental leathers, maki-e lacquerwork, kinpaku gold leaf, standard egawa stencilled rawhide, and imported Chinese silk used for the odoshi of the sode and sangu. The kabuto is a zaboshii-bachi 座星 type with decorative rivets, clearly non-functional in nature, as evidenced by their placement between the suji-tate plates rather than at structural junctions.

Armour with heraldic mon and accompanying sashimono

Hon-kozane maru-dō gusoku

The catalogue describes this armour simply as a suit with shide sashimono, broadly dated between 1700 and 1900. My first impressions, however, were drawn immediately to the feet. The armour is fitted with an unusually distinctive pair of kogake 甲懸, whose form and finish are clearly intentional. They correspond visually with the kote, which have been lacquered in Byakudan urushi nuri 白檀塗. Whether these elements were originally made for this armour or have found a later home with it remains open to speculation, as no other components of the suit are decorated in the same manner.

The dō is constructed from hon kozane 本小札 ,an exceptionally costly method by this period. For its likely date, this construction speaks far more to wealth and status than to practical battlefield utility. By the Edo period, armour of this type would have offered limited protection against spears or projectiles, reinforcing its role as a display object rather than functional equipment.

Another striking feature is the menpō, which bears three circular family crests of the maeda clan in gilded copper, this is also present on the fukigaeshi but in shakudo. This is an extremely unusual treatment, and one I have not previously encountered on a menpō. The haidate and kōhire are edged with fine chirimen crepe silk in a Nanban style, a decorative approach associated with Edo-period embellishment and influenced by European tastes filtering into Japan at the time.

Beyond these distinctive elements, the armour conforms to the vocabulary of high-status Edo-period display armours. It is boldly laced in a vibrant green silk odoshi, with standard decorative treatments including stencilled egawa, prominent ō-sode, and an overall emphasis on visual impact rather than martial pragmatism.

Child’s armour with maki-e dragon decoration

This armour is clearly a composite, an assembly of disparate parts, not a gusoku. However, its significance lies less in formal coherence and more in what it represents. It was customary for a samurai to take his eldest child into battle, and as a result, most children’s armours were assembled pragmatically rather than made as bespoke suits. Children grew quickly, and the cost of producing a complete one off armour was rarely justified.

This example reflects that reality. The cuirass is a hotoke-dō 仏胴 , finely decorated with a gold maki-e dragon. Notably, the dragon is rendered with three claws rather than five, distinguishing it clearly from Chinese imperial dragons or later popular interpretations. The kusazuri are belt mounted and do not correspond stylistically with either the sode or the tare of the menpō, reinforcing the composite nature of the suit.

The kabuto is a chochin-bachi 提灯兜, or folding helmet, which appears entirely out of context here, as this type of helmet is normally associated with tatami armour. Its inclusion further supports the idea of practical assembly rather than aesthetic intention.

The display case also included a range of children’s items, from clothing to indoor archery playsets. This broader context was welcome, drawing attention to an often overlooked aspect of samurai culture. While it would have been preferable to see a more representative example of child-sized yoroi, the armour nonetheless rewards close study, particularly in the quality and application of the maki-e decoration.

Contemporary work by Noguchi Tetsuya

I have included this work by Noguchi Tetsuya simply because his work is extraordinary. Having studied katchū, its history and manufacture, for many years, I find Noguchi’s armour representations to be consistently and uncompromisingly accurate. His attention to detail sets him apart, while his unexpected and often playful juxtapositions have earned him international recognition.

The inclusion of the rubber duck is a genuine delight. Even here, nothing is careless. Details such as the cracked urushi on the tekko of the kote demonstrate a level of observation that borders on obsessive. It is this combination of technical fidelity and quiet subversion that makes Noguchi’s work so compelling.

In Closing

The following images were taken during the exhibition and reflect a range of objects, details, and moments that stood out during my visit. While not part of the selected highlights, they provide useful visual context and further insight into the breadth of material on display.

.jpg)